Participating in the Moose Hide Campaign is an act of reconciliation.

This year, the Vancouver Aboriginal Child and Family Services Society (VACFSS), acknowledged this important event by inviting all men and women in the agency to come forward and pledge their declaration and commitment to stand up against violence toward women and children.

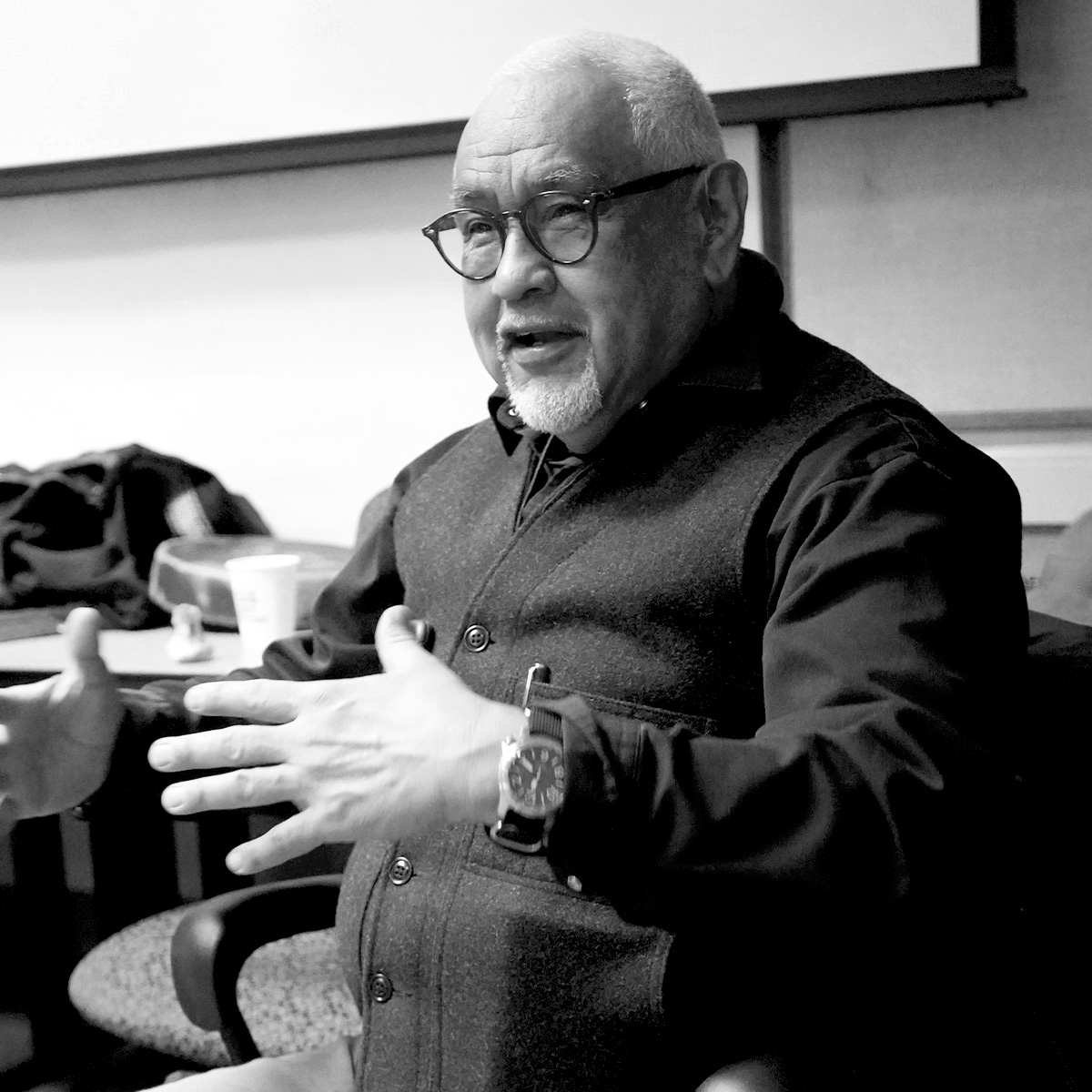

The gathering was opened by Rupert Richardson from the Quatsino First Nation, who shared a song for the children. An empty chair was placed at the center of the room to honour and remember the children who are no longer here because of colonization, or forms of colonization. Elder Shane Pointe, from the Musqueam Nation, was the keynote speaker.

I am here today because I have beautiful daughters, beautiful grand-daughters, beautiful grandsons, and they don’t deserve violence in any form, Elder Shane says. I do my best in terms of language, culture and ceremony, to ensure that they are okay. Traditionally, when historical and ancestral names are passed down, the reason is for protection. I have done my best with my daughters and my granddaughters to blanket them with name, blanket them with ceremony. I give them as much language as I can.

I am here today because I have beautiful daughters, beautiful grand-daughters, beautiful grandsons, and they don’t deserve violence in any form.

In 1960, Elder Shane’s mother stopped the cycle of violence in their home. His father, a residential school Survivor, had never witnessed violence until he attended residential school. There, he endured violence and brought it home with him and inflicted that violence on Elder Shane’s mother. I am grateful to my mom, says Elder Shane.

As a little boy, my aunties would come over to have tea with my mom, and would always ask ‘what she did’ [to make the violence stop]. Everybody heard what my mother was able to do, and everybody wanted the violence to stop against them as well. My aunties and uncles worked to stop the violence. Of course, it was not a movement like it is now.

I had witnessed the violence once as a little boy. It was that once that my mother said to my father, “You need to stop this violence. What you are going to do is teach your son.” Elder Shane’s father, being the good person he is, stopped that very day. When Elder Shane later worked in the prison system, he’d repeat that phrase to the young men he helped, “Don’t do that anymore”. They would say “That’s the first time that somebody has said that to me.”

My nephew was talking to me about being a “Warrior”, and wanting to start a “Warrior Society.” I said to him, “You know, nephew, what you need to do, is not focus on being a Warrior because that could involve violence. Teach the men in the community to be good men.”

Elder Shane says, it’s about becoming who my great-grandfather was – an amazing human being, and a true gentleman. He did not swear or raise his voice, he was kind to his sister, his grandchildren and everyone whom he encountered. That gentleness didn’t negate that he was physically a strong man – a man of culture, language, and ceremony. My great-grandfather was a man of work, a logger, a fisherman, and worked in the mill. Being a gentleman was who he was in terms of his character, his emotion and his intellect.

We need to become one heart, one mind.

Violence is horrible and I don’t condone it in any way, says Elder Shane, but, it is a learned behaviour, and just as you learn the behaviour, you can unlearn it, too. We need to help that 20% of men who are violent. These men were wounded in some way, and it manifests in violence. We cannot be complacent, we need to take action. We need more programs for men, teenage boys, and young boys. We need programs to educate them. We need to speak up and say that “We need to do this.”

I am going to end with the word, “Nutsamaht”. Nutsamaht, translated, means “We are one”. We need to become one heart, one mind. Until we get to Nutsamaht, there will be disharmony.